1. Galileo's Square-Cube Law

Introduction

Gulliver's Travels introduced the fantasy idea that any size is possible.

Does size matter? More specifically, can a rock, a person, a car, a planet, an airplane, or a dinosaur exist at any arbitrary size? This is a fundamental scientific question, and yet, for the most part the scientific community has sidestepped this simple question. Since scientists have not clarified why animals cannot be any size, science fiction writers have had fun playing with the idea that animals can be many times larger or many times smaller than their normal size. While many of us may enjoy the entertaining movies featuring people or other animals at unrealistic sizes, this is not helping to clarify to the public that size truly does matter.

In 1638, Galileo published his book Dialogues Concerning Two New Sciences, in which he clarified why objects cannot exist at any arbitrary size. He explained that when an object is scaled up, its surface area increases by the square of the multiplier, while its volume increases by the cube of the multiplier. Since the ratio between the area and the volume is changing with size the physical properties of the object are changing with size.

In Galileo’s time, the Square-Cube Law was an advanced scientific idea, but today it is a concept that even grade school students can easily grasp. Moreover, Galileo’s Square-Cube Law is not just another scientific principle; it forms the foundation of every major scientific discipline. In fields such as biology, physics, chemistry, astronomy, aerodynamics, and nanotechnology, many fundamental concepts are difficult or impossible to understand without first recognizing that size matters.

Centuries ago, the scientific community made a monumental blunder by ignoring Galileo's insights on the importance of size. Only within the past century has there been a renewed effort by leading scientists to recognize its significance. In 1928, J. B. S. Haldane revisited these ideas in his essay On Being the Right Size, applying them specifically to animals. Since then, other prominent scientists have echoed Galileo's arguments. Physics professors Phillip Morrison, Michael Fowler, and Benjamin Crowell, along with biologists Michael C. LaBarbera, Steven Vogel, Knut Schmidt-Nielsen, Chris Lavers, John Tyler Bonner, and the maverick paleontologist Christopher McGowan, have all emphasized why size matters.

"If an elephant fell from a height of 10 feet, it would be killed. A mouse falling from the same height would be unhurt. The elephant’s bones would break under the stress, while the mouse would have no problem surviving because the ratio of its strength to weight is much higher."

— J. B. S. Haldane, On Being the Right Size

Egyptian Pyramids – Built by stacking large stones, pyramids can reach immense sizes because the stones have high compression strength and pyramids are structurally simple. In contrast, complex objects such as cars, helicopters, and animals are far more limited in their possible size.

So, this begs the question: why is Galileo’s Square-Cube Law left out of science education? One source of confusion lies in the fact that even though changes in size always produce changes in properties, for many simple objects these changes in properties show no adverse effect and so they go unnoticed. For example, most rocks can withstand high compressive forces and so there is nothing preventing the construction of pyramids the size of mountains. In addition to rocks, other simple objects also appear to be unaffected by scaling. However, when we examine more complex systems, such as airplanes or living organisms, it becomes clear that size plays a critical role.

The second source of confusion is the discovery of the exceptionally large dinosaurs that appear to defy Galileo’s Square-Cube Law. How size can determine the properties of objects is an important science concept and science teachers would like to teach this to their students. However, imagine the embarrassment that a grade school science teacher must feel the moment one of their smarter students points out the incongruity between the exceptionally large dinosaurs and the idea that size matters. Paleontologists who insist there is nothing unusual about dinosaurs being so large have put science teachers in the awkward position of either explaining to their students that the paleontologists are wrong or simply skipping over this lesson, which is what happens most of the time. As a result, most people never learn about Galileo’s Square-Cube Law and how size matters.

Explaining the Square-Cube Law

When we are comparing the size of objects it is common to make a statement such as one object is twice as large as another object, without clarifying if the size comparison is based on length, area, or volume. Usually this sloppiness does not cause mistakes since we can infer from the objects being compared whether the comparison is based on a one dimensional, two dimensional, or three dimensional attribute. Yet an important fact that is often overlooked is that the length, area, and volume of similar shaped objects do not scale proportionally.

Of great importance is the ratio between surface area and volume, or — assuming equal densities — the ratio between surface area and weight. Two similarly shaped but differently sized objects will have different area-to-volume ratios: the larger object will have a lower area-to-volume ratio than the smaller one. This seemingly subtle point is fundamental to all of science and must be emphasized: because the ratio between surface area and volume changes with size, it is incorrect to assume that two proportionally similar objects can behave the same. Size matters.

To illustrate how the area-to-volume ratio changes with size, consider a simple cube that is scaled up to be ten times taller. As shown in figure 1, if each dimension of a solid cube is made ten times larger than its original model, its area touching the ground will be 10 x 10 or one hundred times larger. Meanwhile the volume will increase by 10 x 10 x 10 or a thousand times greater than the original. If the larger cube is made of the same material as the original cube, the mass and the weight of the larger cube will be a thousand times greater than the smaller one.

Figure 1. Each dimension of cube B is ten times greater than the each dimension of cube A. Because of this the volume of cube B is a thousand times greater than cube A, while the area of one of cube B’s sides is only a hundred times greater than one of cube A’s sides. Thus, as objects are scaled up in size the volume grows at a faster pace than the area.

If our two cubes are made of the same material then they will have the same density, the density being the amount of mass per unit volume. Yet since the two cubes have different area to volume ratios they will likewise have different stress at the base of each cube. If too much stress is placed on an object then it will either break or collapse.

The stress σ at the bottom of each cube is its weight divided by the area:

\[ \sigma = \frac{F}{A} \]Substituting the equation for weight, \( F = g \rho V \), where \( g \) is the acceleration due to gravity, \( \rho \) is the density, and \( V \) is the volume, we can rewrite the stress equation as:

\[ \sigma = \frac{g \rho V}{A} \]Since volume is given by \( V = L^3 \) and area by \( A = L^2 \), substituting these values and simplifying gives:

\[ \sigma = g \rho L \]

San Francisco's Golden Gate Bridge – To prevent failure, engineers must perform numerous calculations to ensure that every part of a structure is strong enough to exceed the expected stress by a significant margin of safety.

This equation tells us that within a constant gravitational field, while using the same material, the structural stress at the base of the cube increases in direct proportion to the change in the height of the object.

We can understand the relationship between size and stress if we think about why sand castles are rarely more than a couple feet tall. If too tall of a sand castle is attempted the stress becomes too great such that the sand castle crumbles.

In engineering calculating the stress placed on a structure is important to determine that it will be strong enough that it will not fail. For safety reasons, engineers will normally design structures so that the greatest stress expected within a structure is only a small fraction of the known ultimate strength of the supporting material. Table 1 shows the ultimate tensile and ultimate compression strengths of a few selected materials.

Table 1

The Ultimate Strengths of Some Materials

The Ultimate Strengths of Some Materials

| Material | Tensile Strength (MN/m2 ) | Compressive Strength (MN/m2 ) |

|---|---|---|

| Steel | 500 | 500 |

| Concrete | 2 | 20 |

| Nylon | 75 | ### |

| Bone (limb) | 130 | 170 |

A skyscraper in Chicago – The high strength of the steel framework enables the construction of such tall buildings.

Let us combine what we have learned from the cube example with the fact that materials have a limit to the stress they can withstand. Suppose we want to construct two buildings using either the same materials or materials with nearly the same density. Building A will be a single-story model apartment, while Building B will be a ten-story, thousand-unit apartment complex. From our cube example, we know that stress is greatest near the bottom of each building. However, because stress is proportional to height, the stress near the base of Building B will be ten times greater than that near the base of Building A.

For the single-story building, concrete could be a suitable choice. One-story concrete buildings are common because concrete is relatively inexpensive and strong in compression. According to the table, the ultimate compressive strength of concrete is listed as 20,000,000 N/m2. However, for a ten-story building — and certainly for taller structures — steel would be a better choice, as its compressive strength is twenty-five times greater than that of concrete.

In Jonathan Swift’s 1726 novel Gulliver’s Travels, Gulliver visits lands where the people of Lilliput are twelve times smaller than himself, while in Brobdingnag, they are twelve times taller. While this makes for an entertaining fictional story, it does not align with reality.

From the table, we see that bone, like other materials, has a fixed ultimate strength. Unlike buildings, however, vertebrates are limited to just one type of supporting material — bone. A proportionally scaled Brobdingnagian would experience twelve times greater stress on their bones. This excessive stress would cause their leg bones to snap after taking just a few steps. Clearly, then, Gulliver and the giants of Brobdingnag cannot be proportional in their dimensions as the story claims.

Effect of Scaling Properties on Biology

Returning to reality, there are species of animals, such as deer and elk, that are closely related but differ in size. Galileo observed that the bones of an elk are not just proportionally thicker than those of a deer — they are significantly thicker. This increased thickness is necessary to reduce the stress on the bones below their breaking point. Even so, elk and other large vertebrates are still more likely to break their bones than smaller, more active animals.

The bones and muscles of the larger animals tend to be disproportionally thicker and larger than the smaller animals. Yet the smaller animals will still have the greater relative strength that allows them to jump higher and fall greater distances with less chance of breaking their bones.

The Square-Cube Law applies to the skeletal structure of vertebrates in the same way it applies to non-living objects. If an animal is twice as tall as a similar species, the cross-sectional area of its leg bones increases fourfold, while its weight increases eightfold. This means that the stress on its bones is twice as great, making the larger animal much more prone to bone fractures. Due to these scaling properties, larger terrestrial vertebrates are at a significantly higher risk of breaking their bones than smaller ones.

A cat that has climbed up a tree is not worried about falling and it will be annoyed if you try to rescue it.

When an animal lands after a fall, the stress on its leg bones is many times greater than when it is standing still. Therefore, all animals must have bones that are significantly stronger than what is required for simply standing. Additionally, much like the engineering design of man-made structures, an animal’s bones must be built with a substantial safety margin — many times stronger than the bare minimum needed to withstand the greatest expected impact.

Due to scaling properties, larger animals are at a greater risk of experiencing stresses that exceed the ultimate strength of their bones, leading to fractures. This principle explains why small animals, such as cats, often survive falls from great heights unscathed, whereas a racehorse can suffer a catastrophic leg fracture simply by running.

The Square-Cube Law also affects muscle strength. Both muscle and bone strength are proportional to cross-sectional area (L2), while an animal's weight is proportional to volume (L3). As a result, smaller animals have a much higher muscle-to-weight ratio than larger animals. For example, an ant can lift fifty times its own weight, a human can lift roughly its own weight, and an Asian elephant can only lift about 25% of its own weight. This superior muscle-to-weight ratio allows smaller animals to jump several times their own height, whereas an elephant cannot jump at all.

In summary, while larger vertebrates generally have greater absolute muscle and bone strength than smaller animals, their strength-to-body-weight ratio is significantly lower. The larger the animal, the lower its relative strength.

The Effect of the Surface Area to Volume Ratio

Another important scaling property is the surface area to volume ratio. Again using the example of the cubes, the total surface area of the smaller cube is 6 L2 and its volume is L3. The surface area to volume ratio for the small cube is then 6 / L. Performing the same calculations with the larger cube produces a surface to volume ratio of 6 / (10 L). So that a comparison of the two ratios shows that the cube that is ten times larger has a surface to volume ratio that is one tenth of the smaller cube. From this we can draw the general conclusion that larger objects will have lower surface area to volume ratios than similar smaller objects.

To start a fire, we light small twigs and then gradually add larger sticks.

The surface area to volume ratio can be important to determining the rates of chemical reactions, diffusion rates, the rate of heat loss, and many other phenomena that are impacted by sizing variables. For example, one of the best ways of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction is to increase its surface area to mass ratio by pulverizing the reactive substance into a fine powder. By breaking large pieces into smaller pieces the overall surface area available for reaction increases.

A campfire is a chemical reaction that changes solid wood into various gasses while giving off heat. Yet heat is first needed to get this chemical reaction to take place and when the fire is first started there is not much heat available. We overcome this problem of starting the fire by using the small twigs rather than the logs so that more wood is exposed at the surface to participate in the reaction. This allows the fire to grow from only the modest heat from the lit match.

Similar to what is best to speed up chemical reactions, to maximize the rate of diffusion it is desirable to have the largest surface area possible while keeping the separating membrane as thin as possible. For vertebrates, it is desirable to have a high diffusion rate within the lungs and the cardiovascular system’s capillaries, so it is not surprising that these diffusion systems have large surface areas with thin membranes.

| Material | Thermal Conductivity (W/m*K) |

|---|---|

| Aluminum | 200 |

| Steel | 20 |

| Glass | 1.1 |

| Concrete | 0.84 |

| Human Tissue | 0.2 |

| Styrofoam | 0.025 |

Diffusion rates are extremely important to the smallest recognized living unit, the single cell. Most eukaryotic animal cells are within a range between 10 and 30 micro meters. The size limitation of these and other cells is due to the diffusion process for transferring nutrients and waste across the cell’s membrane. A cell’s surface area to volume ratio, or likewise its surface area to mass ratio, decreases as the cell grows larger. This lower surface area to mass ratio slows down the diffusion rate and along with this the metabolism of the cell thus causing a larger cell to be less efficient than a smaller cell. So to keep an overall high efficiency throughout the body the larger cells will divide rather than continue growing. Thus multi-cell animals grow by increasing the number of cells rather than increasing the size of the cells.

The surface area to mass ratio is important to the transfer to thermal energy: heat. Whenever there is a difference in temperatures, thermal energy travels from one location to the other through conduction, convection, or radiation.

Conduction is the transfer of heat through a solid material such as when one side of a metal object is heated the heat easily distributes itself throughout the entire object. Different materials conduct heat at vastly different rates. So we need to choose the appropriate material when the transfer or lost of heat is an issue.

For example, previously aluminum window frames were preferred over wood frame windows because, unlike wood, the aluminum windows did not rot. However, as people became more energy conscious they recognized that aluminum framed windows had their own undesirable attribute in that they allowed heat to easily moved between the inside and the outside of the home. Because of this, double pane vinyl windows are now the most preferred window frames because they are both good thermal insulators and highly resistant to rotting.

The fire is giving off radiant heat.

Convection heating occurs through the movement of a warm fluid from one location to another. When there is a difference in temperature between two locations and there is a fluid that is free to flow between those locations a natural convection current will establish itself to transfer heat from the hot location to the cool location. If this transfer of thermal energy is undesirable then it is best to impede the flow of the fluid. For example, the primary way that clothing and coats keep us warm is due to the fibers in the clothing and insulation that get in the way of a free flowing current of air. Insulation that traps or slows down the movement of air is also used to keep homes warm and to keep hot beverages hot. Even though these insulating materials such as fiberglass and Styrofoam are rated as if they are preventing the conduction of heat they actually work by stopping the convection process by stopping the flow of air.

Radiation is the transfer of heat by electromagnetic waves, light, traveling through space from a warm location to a cooler location. Radiation is unique in that it transfers thermal energy from a hot location to a cool location without the need for there being anything in between the two locations. If not for radiation, the warmth of our Sun would never reach Earth.

On Earth, if we have an object that is isolated from other objects, then usually only the convection process of the flow of air or water or the radiation through space will allow heat to be transferred to or from the object. How much heat will be transferred through either the convection or the radiation process will depend on several variables and included among these variables is the surface area to mass ratio.

Since there are many variables that affect heat transfer but we just want to focus on how size affects the rate of heat transfer, let us imagine once again that we have two objects that are the same in all respects except that they are different in size. If the two objects are heated to the same temperature and then allowed the cool, the smaller object with its higher surface area to mass ratio will cool off faster than the larger object. Furthermore it does not matter if the objects are cooling off or heating up the smaller object will change its temperature faster than the larger object.

When preparing a banquet, a large turkey or ham is usually placed in the convection oven first because these larger items have a low surface area-to-mass ratio, requiring more time for heat to penetrate to the interior. In contrast, foods like pizza, with a high surface area-to-mass ratio, cook much faster. For example, while a Thanksgiving turkey needs about hours in the oven, a pizza only requires about 14 minutes.

Puppies stay warm by sleeping together.

For another example, a large iceberg floating in warm water will usually take several months to melt. Yet if we took that same iceberg and divided it into millions of refrigerator size ice cubes then all of this ice could be melted in no more than a few minutes. The size of objects is often the most important factor determining the rate of heat transfer per unit mass.

Often, rather than heating up or cooling off, it is desirable for an object to be maintained at an elevated temperature above the temperature of its surroundings. To maintain this constant elevated temperature thermal energy must be added at the same rate that the object is losing heat at the surface. Since thermal energy is usually expensive we want to reduce this lost of energy as much as possible. One of the best ways to minimize this energy lost is to reduce the collective surface area to volume ratio of the group. For this reason, it will usually be much cheaper to heat a single apartment unit than to heat a house with the same amount of interior space. Conservation of thermal energy is also the reason many animals from bees to puppies huddle together to stay warm.

Applying Thermal and Scaling Properties to Understanding Mammals and Birds

Mammals and birds are more complex than reptiles because maintaining a constant elevated body temperature requires several unique adaptations. These adaptations grant mammals greater mobility and enable them to inhabit colder environments, such as the mid and upper latitudes of the Earth, or adopt nocturnal lifestyles. However, these benefits come at a cost, as they demand significant physiological adjustments to sustain their high-energy needs.

Small animals eat huge meals.

First, since a mammal or bird’s body temperature is almost always greater than the surrounding temperature, heat is continuously being lost to the surroundings. This thermal energy is expensive meaning that mammals and birds must consume a large quantity of food to compensate for the lost of this thermal energy. For nearly all mammals or birds, the amount of food energy that goes towards keeping warm is greater than the amount of food energy that goes towards mobility. For the smaller mammals and birds, having a higher surface area to mass ratio, the constant consumption of food to maintain the required elevated body temperature is a primary concern of survival.

The smallest endothermic animals, such as mice, bats, and hummingbirds, have the highest surface area-to-volume ratios, resulting in a rapid rate of heat loss relative to their total body mass. To replace the thermal energy they lose so quickly, these small animals must constantly move to find and consume as much food as possible. Their daily food intake can exceed one-third of their total body weight. To cope with the challenge of consistently needing enough food to compensate for their constant loss of thermal energy, these small warm-blooded vertebrates have adapted their behaviors. For example, to minimize heat loss, mice huddle together, bats hang from ceilings where it is warmer and potentially more secure, and none of these small animals inhabit extremely cold environments.

At the other end of the spectrum, elephants have a much lower surface area-to-mass ratio, which presents the opposite challenge: they need an effective way to remove excess heat from their bodies. The evolutionary solution to this problem is their large ear flaps, which serve primarily to radiate heat rather than enhance hearing. Elephants pump warm blood to the skin of their ear flaps, where excess heat is dissipated through convection and radiation. As the largest mammals living in warm climates, elephants are clearly an exception among most other mammals, as their primary need is to lose rather than maintain heat.

Almost all mammals and birds aim to slow the loss of thermal energy. This is why mammals are covered with hair, which traps a thin layer of air close to the body, serving as insulation against the cold. Similarly, birds are covered with feathers, which also trap air and insulate them from the cold. In general, feathers provide slightly better insulation than hair, allowing birds to maintain a higher body temperature than most mammals.

Notice that the shape of the mouse is as close as it can be to that of a sphere, a shape that produces the minimum amount of surface area. Now notice that the elephant’s skin is covered with wrinkles thus increasing the elephant’s surface area. Also notice that the mouse is like nearly all mammals in being covered with a thick fur coat while the elephant is nearly void of all hair. The small mouse is trying to maintain heat while the large elephant is trying to lose it.

Mammals and birds that spend significant time in water cannot rely on trapped air for insulation, so they use body fat instead. Due to the challenge of heat loss, most mammals living in the ocean or polar regions tend to be large, with a thick layer of fat just beneath their skin. In these harsh environments, a lower surface area-to-mass ratio—resulting from their large size—and insulating fat are essential for preventing excessive heat loss and maintaining body temperature.

Warm-Blooded Babies

Unlike the reptiles, a human baby could never be mistaken for a miniature adult.

Unlike man-made objects, animals grow as they transition from newborns to adults. This growth varies among vertebrates depending on whether they are cold-blooded or warm-blooded. Reptiles, being cold-blooded, do not internally regulate elevated body temperatures, so heat loss is not a concern for them. As a result, their growth is straightforward, with baby reptiles resembling miniature versions of adults. In contrast, mammals and birds must maintain elevated body temperatures throughout their lives, transitioning from having a low mass and high surface area-to-mass ratio at birth to high mass and low surface area-to-mass ratio in adulthood. Warm-blooded babies face difficulty maintaining a consistent body temperature due to their small mass and relatively large surface area. To minimize heat loss, mammal and bird infants start life with rounded features, relatively large heads, and proportionally smaller limbs compared to adults.

Relatively speaking, warm-blooded (endothermic) babies need to be much larger at birth than cold-blooded (ectothermic) reptiles. This is necessary because maintaining a constant elevated body temperature poses challenges for warm-blooded animals — challenges that reptiles do not face. The larger size required at birth for warm-blooded vertebrates results in fewer offspring per gestation. As a result, mammals typically produce one to ten offspring per gestation, while reptiles often produce ten to a hundred offspring per reproductive cycle.

Furthermore, a warm-blooded vertebrate’s need for a consistently warm environment at birth helps explain why some mammals and birds have multiple offspring per gestation, while others typically have only one. This difference depends on whether the species can find or create an insulated den or nest to keep their newborns warm during their earliest days. Species with access to such shelters — like rabbits, dogs, and lions—can successfully raise several young at once. Similarly, birds lay eggs in nests and incubate them by sitting on them until they hatch. In contrast, many large mammals — such as apes, elephants, and whales — find it difficult or impossible to obtain a den, and as a result, these species usually have only one offspring per gestation. There are also some smaller species, such as penguins and bats, which likewise face challenges in providing a warm environment for their young thus limiting them to a single offspring per gestation. For example, male emperor penguins keep a single egg warm by balancing it on their feet and covering it with a fold of skin. Likewise, mother bats delay giving birth until the pup reaches about 25% of their body weight, thus ensuring that the pup can survive cold nights without succumbing to hypothermia when it is left alone.

The importance of mammals maintaining a constant body temperature is illustrated by the outdoor guide's "rule of three". A person can survive for three weeks without food, or they can survive for three days without water, yet if a person does not have adequate insulation from the cold they can be dead within three hours.

This is just a short introduction to some of the important scaling properties that are general to all objects.

Fundamental Forces of Nature

Size matters because the surface area to volume ratio changes with size, and this changes the properties of the object. Yet this is not the only reason that size matters.

Science has identified four fundamental forces of nature and these forces of nature dominate at different ranges of size. So from a completely new perspective from Galileo’s scaling properties, once again, size matters. The four forces of nature are the strong and weak nuclear forces, the electrostatic / electromagnetic force, and the gravitational force.

Lighting Strike

The strong and weak nuclear forces operate over very short distances, just slightly larger than the typical nucleus. The strong force holds the nucleus together, while the weak force is believed to play a role in radioactive decay. The electromagnetic force, on the other hand, operates across a wide range of scales—from the size of individual atoms to the vast distances of magnetic field lines that produce sunspots. Electrostatic attractive and repulsive forces arise when there is an imbalance of positively charged protons or negatively charged electrons. In a region with only positive charges, those charges will repel each other. Similarly, in a region with only negative charges, the negative charges will also repel. owever, when both positive and negative charges are present, the oppositely charged particles will be attracted to each other.

An example of opposite charges coming together can be seen in dramatic lightning strikes. However, the electrostatic force is most notable for its effects at the atomic or microscopic level, where it is easier for there to be one or two extra or fewer electrons, creating an unbalanced charge. These small electrostatic forces are the basis for chemical bonds. Thus, far from being insignificant, these forces operating at the microscopic level ultimately determine the properties of nearly everything in our world.

The gravitational force is a weak attractive force that acts between all matter. It is so weak that it often goes unnoticed unless there is at least one extremely large object nearby. For those of us living on the surface of the Earth, the most significant large object is, of course, the Earth itself. In addition to attracting us to its surface, the gravitational force holds the Moon in its orbit around the Earth and keeps the Earth in its orbit around the Sun.

The purpose of this discussion on fundamental forces is to highlight that each type of force tends to dominate at different ranges of size. At the level of planets and stars, gravitational forces are of primary interest. However, when we examine smaller scales, such as that of a small insect, electrostatic forces can be just as significant as gravity. At the even smaller scale of bacteria, electrostatic forces become the only relevant forces, rendering gravity negligible. By considering which forces are important at various sizes, we can develop a better understanding of our reality.

While size is important to the fundamental forces, the effects of changing the size of an object are more readily apparent when considering Galileo’s Square-Cube Law. With fundamental forces, we typically need to consider a massive change in scale—such as one object being millions of times larger or smaller than another — before we observe a noticeable difference. In contrast, the Square-Cube Law reveals significant differences, and even catastrophic failure, in many objects simply by doubling their original size.

Fundamental Science

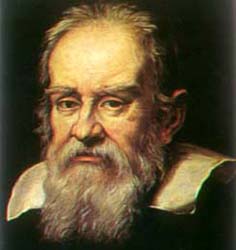

Galileo Galilei

The two most important books of Galileo were Dialogues Concerning Two Chief World Systems and Dialogue Concerning Two New Sciences. In Dialogues Concerning Two Chief World Systems he showed the compelling evidence in support of Copernicus’ heliocentric model of the solar system while in Dialogue Concerning Two New Sciences he presented the arguments regarding the importance of size. Galileo’s explanation of how the Earth orbits the Sun played a critical role in sparking the Scientific Revolution, which laid the intellectual foundation for the Age of Enlightenment. However, his equally important insights into scaling laws, presented in Two New Sciences, were largely overlooked by the scientific community.

Currently, nearly every scientific and engineering discipline — from aerodynamics to biology to nanotechnology — tends to assume that the scaling challenges they encounter are unique to their field. However, understanding how size influences the properties of objects lies at the foundation of science. Galileo’s Square-Cube Law offers profound insight into how size and scale govern the behavior of objects and organisms in our reality.

Now that the importance of Galileo’s Square-Cube Law is established, how do we explain the exceptionally large dinosaurs and flying pterosaurs? In the next two chapters, we will explore the logical challenges these massive creatures present, and in chapter four, we will search for a resolution to these scientific paradoxes. We live in a rational universe, and there is a solution to the large dinosaur paradox.

Videos

External Links / References

Physics of Size

- Scaling: the Physics of Lilliput - Phillip Morrison

- Introduction to Scaling Laws - John Denker

- When Big Science Goes Wrong - ASTRONOMY BLOG

- The Principle of Scale: A fundamental lesson they failed to teach us at school - Leon Bambrick

Strength of Materials

- Strength of Materials Definitions and Equations - ENGINEERS EDGE

- Stress and Strain Equations - MechaniCalc, Inc.

- Strength of Materials Video Tutorials - Engineers Reference

Physics, Biology, and Scaling Properties

- Of Mice and Elephants: a Matter of scale - Geoffrey West

- On being the Right Size - J. B. S. Haldane

- Surface Area to Volume Ratio - Bernie Hobbs

Scaling Properties and their Application to Biology

- The Biology of B-Movie Monsters - Michael C. LaBarbera

- Scaling: Why Giants Don’t Exist - Michael Fowler

- From Cells to Whales: Universal Scaling - SCIENCE NEWS

- Basal Metabolic Rate - David M. Harrison

Size of Biological Cells

- Diffusion and the Problem of Size - BIOLOGYMAD

- How Surface Area to Volume Ratio Limits Cell Size

- Minimal Protocell Size and Metabolism - PACE

Surface Area to Volume Ratio

Heat Transfer

Heat Transfer in Regards to Mammals

- A Mouse like a House? A Pocket Elephant? - SMITHSONIAN

- Animals Heat Transfer - Kimball's Biology

- Animal Survival in Extreme Temperatures - ACS